this is what being online should feel like

Before scrolling and algorithms, there was “surfing the web.”

I became a bit obsessed with this idea a few months ago.1 And, despite having almost no lived experience with the early internet, it’s always fascinated me. Today the online world feels everywhere, omnipresent. But what about when it used to be somewhere? When the internet was a place you could visit, explore, and return to every once in a while?

Most of what I know about that era comes through abstraction. Like a game of telephone, I’ve only picked up bits and pieces—Myspace, AOL, chain emails. “The internet used to make a sound?” I ask, and my friend (older, wiser) nods and smiles serenely, like a cat. Years later, I finally look up the sound of dial-up Internet and find a Youtube video. A grating, yet charming sequence of futuristic noise plays through my headphones. I close my eyes and imagine I’m sitting patiently in the hull of a spaceship.

Maybe what’s most interesting about the early internet is the way it was shaped by collective desire. People wanted to express themselves, so they did. They reached into a digital void for community, and found it. When I picture “surfing the web,” I see DIY websites with neon font on dark backgrounds, Y2K cursors that move across the screen in a trail of pixelated glitter, silly home videos, and message boards about TV shows. I don’t think of monetization, or influencers, or quantitative metrics. Was it really that wacky and wholesome? Or does my undeserved nostalgia—yearning for an internet I never knew, one that existed before me—tint everything with a soft glow?

I want to believe my experience of the internet can still transcend what I’ve been given. I want a digital life that’s non-hierarchical, multiple, interconnected. Maybe the exploratory spirit of “web surfing” offers a way back to that possibility.

Scrolling, for me, is second nature: an endless upward flicking motion, like pulling the lever of a slot machine. “Surfing the web” is different. It’s horizontal, rhizomatic, curious—a self-guided journey through desire.

Think of rhizomes in the literal, botanical sense: stems that grow sideways, sending out roots and shoots from every node. Ginger, turmeric, iris, and bamboo grow this way. They are plants that spread laterally, not vertically, to create sprawling networks. Hello, internet! We call it “the web,” but a web has a center, a pattern radiating out from one point of creation. In reality, the internet is much stranger and more radical: an endless rhizome of energetic sinew and binary code. What would it be like to use it that way, to appreciate the internet for what it is and could be?

I’m thinking, here, about Poetics of Relation, one of my all-time favorite theory books, written by French-Caribbean poet and philosopher Édouard Glissant. For Glissant, the rhizome is a model for how cultures, identities, histories and languages interact—not as isolated, pure, or self-contained entities, but in constant relation, shaped by contact and exchange.

Seen through that lens, web surfing naturally challenges digital totalitarianism. It’s easy to assume algorithms define our entire online experience; we can effortlessly rely on corporate machines to curate our desires. But web surfing destabilizes that dominance. There was a way to be online without the algorithmic gaze. There still is. The totality of the internet is not inevitable.

Glissant writes:

“...in the poetics of Relation, one who is errant (who is no longer traveler, discoverer, or conqueror) strives to know the totality of the world yet already knows he will never accomplish this—and knows that this precisely is where the threatened beauty of the world resides.”

There is an errant beauty in web surfing, a form of exploration corporations have quietly pushed to the margins. But it’s still there, waiting for us to step outside habit and set our curiosity free.

Recently, I’ve been practicing it. After a day of working, writing, and making music, I sometimes set aside an hour of pure “computer time.” I pretend I’m in 3rd grade again, logged onto a library desktop, and the online world is my oyster.

The other day, I went to Youtube and told myself I could only use the search bar. No clicking on recommended videos, no autoplay. I looked up a song I love, “Onde Sulla Riva” by Armando Trovajoli, and let the dreamy sound of late-60s Italian cinema wash over me. Then, I thought, “Who is Trovajoli?” and searched for his Wikipedia page. One tab led to another: his filmography, then actress Laura Antonelli, then a quick realization that she died on my birthday, decades before I was born.

Feeling a bit playful and morbid, I wondered: “Okay, but who died on my actual birthday?” A Google search told me: Luboš Fišer, a Czech composer, died June 22, 1999. “Less than six months from the new millennium,” I thought. Maybe he surfed the web, too.

I read about Fišer for a while, amused by what a few lazy clicks had unraveled. The song ended, and Youtube’s autoplay immediately started something else—one of the oldest algorithms I know, reclaiming me. “Well,” I thought, “I tried. And I learned something new.” To stay faithful to the historical accuracy of a 2008 library computer session, I dutifully navigated to coolmathgames.com for the first time in years.

I kept web surfing for a while. After about 30 minutes, I was ready to return to my real life. But it was unlike the restlessness that usually follows too much social media. I was happily satisfied with my time online. Content, even. A rare feeling.

I liked this way of being online, one that prioritized my own desire and agency. I even started a list in my journal: websites I love, digital magazines to revisit, YouTube channels, albums to find. It felt like I was getting away with something. Better yet, it felt like memorizing the location of landmarks in my city and finding a way to get there without GPS.

Later, when I picked up my phone for a “quick hit” of social media, I was surprised by my annoyance with the usual stream of content. “I want to watch what I want to watch,” I remember thinking. “They don’t have what I’m looking for.” I kept scrolling anyway, feeling sticky and gross.

How could I be so dissatisfied, and still want more? I felt disgusted with myself, and then with them, for holding my attention so easily. A website only has to study my behavior and mirror it back, and I’m hooked. The seductiveness of the internet is disturbing, but the most disturbing part is always my reflection staring back.

Mirrors, after all, are relatively new to humans. Early humans rarely saw themselves clearly—mostly in the eyes of others, or in rare pools of still water. My life, on the other hand, is full of mirrors: literal, metaphorical, digital. Some days I can’t stop looking. I crave it, even. The internet-mirror has always been there for me. I’ve never known a world without it, a fact that amuses and unnerves me in equal measure.

And yet, I’d be lying if I told you that you should stay offline entirely. I love my analog life, my offline soul. And I also love the dizzying, endless beauty of the internet, without shame.

Since I was a kid, I have relished the internet as my simulacrum away from home. I’ve always loved the things that could happen online, the ways it transformed my real life in ways only I understood. I have kept secrets online, and I have shared them. I grew up here, and I’m still growing.

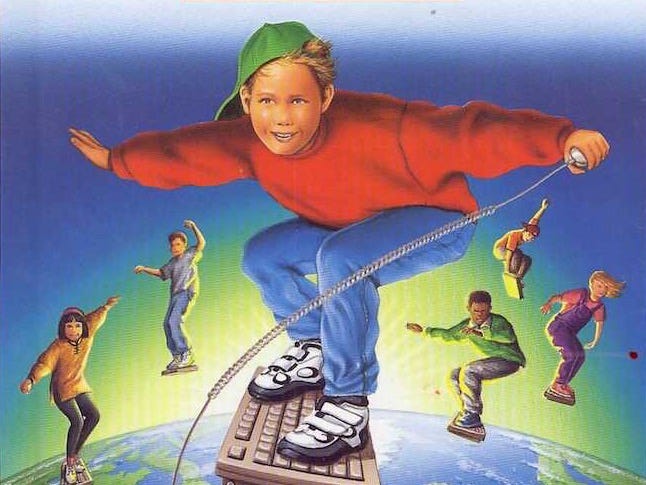

Maybe that’s what the internet can be, at its best. “Surfing the web” is a dated, slightly cringe phrase, but it has contemporary potential. I imagine myself crouched on a floating keyboard, riding the waves of my own curiosity. The internet feels pervasive when you’re constantly connected, but it doesn’t have to be. Going online is a choice, and we can choose how and when to engage.

When I try my hand at “surfing the web” these days, it feels like riding a bike. A bit clunky at first, but smoother than expected. The hardest part is knowing where I want to go. And that’s a good problem to have.

Thank you for reading this essay! I’m Dani Offline—musician, writer, and human girl. Offline Soul is a reader-supported publication. If you’d like to help make my writing possible, consider upgrading to a paid subscription <3

The idea for this essay came from a post I made back in August. I loved reading the comments, and want to thank everyone who responded to that random thought. You inspired me to say more about it!

Yes yes yes! Bring back wonder and curiosity to the internet. I think the way we create more life in the digital space is by coming to it on our own terms and stop allowing billionare tech bros tell us what we like and don't like. One resource I've thoroughly enjoyed is called Cloud Hiker. It's a site that literally allows you to surf the web. I've come across so many cool websites in this way.

"Today the online world feels everywhere, omnipresent. But what about when it used to be somewhere?" What an interesting way to put it. Might I offer that "surfing" the internet was a more fitting verb when we *had* to choose our waves to surf? With the "algorithmic gaze" (as you had wonderfully described) of being online, scrolling through a feed that's automatically curated for you feels like the ocean currents are deciding where you have to go. Perhaps surfing the internet was a more popular phrase when the water was shallow enough for us to reach the air. Today, surfing sounds like an exhausting thought when you can just let the waves of algorithms seize you. New fan to your page, absolutely fun read! I'll be using more of my search bar from now on ;)